Liutprand of Cremona was a Lombard diplomat born in the early 10th century into a noble Lombard family. As a young man, he distinguished himself at the court of the ruler Hugo of Arles (926-945) with his knowledge and diction. He received his education at the court in Pavia, and later became a deacon of the cathedral in Pavia. After that, he entered the service of the Berengar II, who sent him to Constantinople on a diplomatic mission.

At that moment, Constantine VII Porphyrogenitus (905-959) was at the emperor of Byzantine Empire. Liutprand prepared for this trip by trying to learn as much as possible about the history and culture of the empire there. He even tried to learn basics of Greek language. His first visit to Constantinople was positive, which can be seen from his writings.

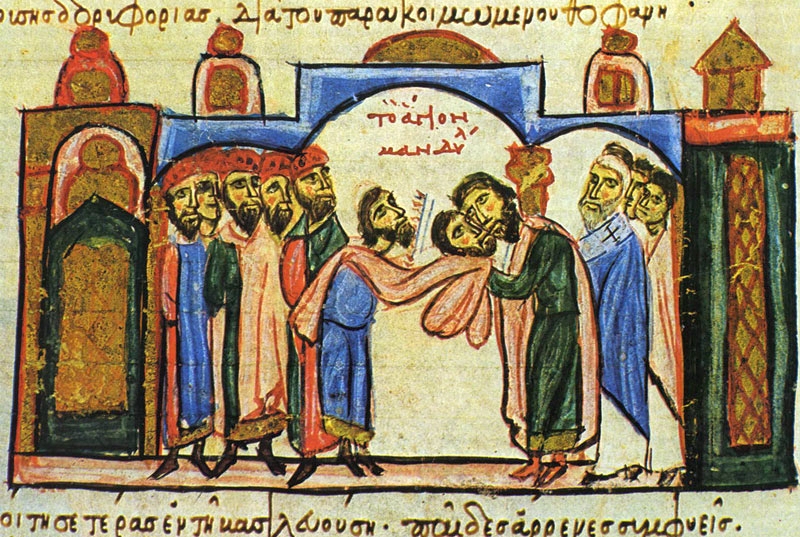

At first he was delighted with the palace called Magnaura where the emperor welcomed him. In the hall was a throne for the emperor and a gilded bronze tree on which Liutprand saw various birds singing differently. He also described decorative lions that stood gilded and made a roaring sound. Liutprand describes the emperor’s demeanor as unusual and “ill-mannered. He does not speak to the diplomat directly but through a logotet. Of course, this western diplomat did not understand this behaviour due to simple cultural differences.

Liutprand ‘s Observations in Byzantium

After the meeting with the emperor, the diplomat notes the other wonders of Constantinople. One of them is eunuchs, castrated boys, which he learns were at a high price and are often sold in Hispania. He then describes the “Hall of 12 Beds” which was next to the Hippodrome. This building was a sort of reception room for guests, who get food and drinks there. Diplomats caught the eye of the golden bowls in which fruit was served and the games that accompanied the meal.

The last thing he described during his first visit is the custom of giving gifts to military leaders and government officials during Palm Sunday. Liutprand speaks of a long table in the hall on which bags of money were lined up, which were then distributed to officials. Despite his shock at these traditions, Liutprand gladly accepts his gift from the emperor and thus ends his narration.

SUPPORT

You like our content? Consider following us on our social media platforms here for more updates on our content!